Musubi : On Grief, Connection, and Boundaries

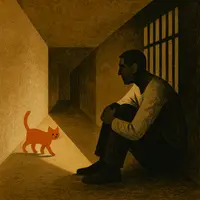

The cat was near death when Alicia’s eldest daughter Cora found him wedged in a crawlspace beneath the restaurant’s patio. The dying animal lay heavy and inert in Alicia’s arms like a black duffle bag. Twigs and leaves stuck to the stray’s bloodied mouth. His one good eye assessed me coolly.

“Momma, is Musubi gonna be okay?” sobbed Dalia, the youngest daughter, her crinkled face shining in the morning sun. The three of them had been standing in the empty parking lot when I arrived.

“He’s going to be fine, sweetheart,” Alicia lied. To me she said, “Maybe we should take him to a vet.”

It was agreed that I would drive, as I knew of a clinic up the road. The five of us took off, the kids in the backseat, excited and asking too many questions, Alicia in the passenger seat with the cat pressed to her chest, the car’s seat belt alarm dinging on account of her seat being unbuckled.

It was Alicia who’d named the cat Musubi after the popular Spam appetizer we serve at the restaurant. In actuality, Musubi didn’t care for Spam but preferred the chopped baked chicken I’d begun to feed him by the handful when he first started coming around the patio months ago. He was suspicious in the beginning, as cats often are. Twice the bartender got a swift swipe across the arm for getting too close too soon. And while he eventually warmed to us, allowing himself to be petted, his rump scratched, I noted that I was the first recipient of these affections.

The servers noticed too and took to calling me the stray’s “dad.” They encouraged me to take him home, but I assured them that Musubi was no one’s cat but his own. When he wasn’t stretched out on our patio sofa, one might see him slinking through the neighborhood’s gentrified lawns, threading the alley behind the taqueria and pizzeria, or holding court at the bar down the road, where a colony of younger cats lived, each one’s coat streaked black. The city was his home. He was well fed, his coat thick and glossy, his face scarred above the nose and left ear. Clearly, he needed no saving. He may have allowed us to pet him, but only after emitting a hiss to let us know he had boundaries. He was not a cat meant for captivity.

From the backseat Dalia sobbed extravagantly. I glanced at her in the rearview mirror sitting beside her older sister, her tiny moppet face a dark cloud bank of grief. I averted my eyes. Having the children in my car made me nervous. Having children anywhere near me made me nervous. They seemed unknowable, combustible. They were sticks of dynamite strapped to my backseat. During the winter and summer breaks, when not in school, Alicia brought them with her to the restaurant where they’d sit at table forty-one to color or sleep or watch cartoons on their tablet computers. Or else they might play on the patio, inventing games and building forts with the tables and umbrellas (this was precisely how they happened across Musubi that morning in the throes of death).

Less often but more terrifying were the times Cora and Dalia would run through the kitchen—my domain—playing tag or swiping bread and caramel sauce. Alicia might stick her head through the pass and yell, “You know you’re not supposed to be in there!” I appreciated her keeping her daughters out of the way, as the rules of my probation prohibit me from being around minors unsupervised. But I wondered sometimes whether Alicia’s reproach was for my sake or for her kids’. Kitchens are undoubtedly dangerous, filled with flames and blades and slippery surfaces. But was it possible that Alicia saw me as the real danger?

She’d never asked me directly about my charge, which I assumed meant that she knew everything she needed to know and was too polite to pry. Surely she wouldn’t have continued to employ me if my presence made her uncomfortable, or send me Christmas cards adorned with family portraits, or invite me to her home for Thanksgiving—a harrowing function, it turned out, in which I spent the evening chained to the adults while simultaneously dodging her rambunctious, sticky-fingered daughters.

I comforted myself by reaching over to the passenger seat and scratching Musubi around the collar. From the backseat, Cora helpfully postulated a list of possible diagnoses for the dying cat: An upset tummy. A fight with another kitty. A hit and run.

“I don’t know, honey,” Alicia repeated absently.

The veterinarian’s office was spacious and well-lit with orderly arrangements of brightly colored furnishings intended to give the impression that here was a place where any wrong could be righted. I felt immediately at ease as the receptionist ushered us through the clinic, past a woman describing the color of her chow mix’s poop, and into a large private room with an examination table and sofa. Alicia set Musubi on the table and held him steady, though he showed no interest in escaping. His one good eye, the one not clamped shut and leaking, stared noncommittally at me leaning against the wall. The children sat on the sofa.

“Dalia, honey, please don’t cry. They’re going to fix Musubi good as new,” Alicia said, looking at me. It was a good thing I would never become a parent; it required telling too many lies.

A technician in cornflower blue scrubs came in shortly to take down the cat’s information and vitals. Pressing a stethoscope to the animal’s fluttering ribcage, she asked us the cat’s age. We told her we didn’t know. “Where does he stay?” We weren’t sure. “But who cares for the cat?” We couldn’t say. It must have dawned on us then that what the technician was most interested in was which of us would be footing the bill, because Alicia and I looked at one another then with raised brows, each silently asking the other just how deeply involved we were willing to get with this animal. I consulted my watch. The restaurant would be opening in a half hour. It was a chilly morning and promised to be busy.

The technician went away and was replaced by the veterinarian, a crisp, polite woman clearly versed at breaking bad news with courteous dispassion. She suggested the children step outside. There were crayons and coloring books. Musubi, for the first time, attempted to stand. He looked at me with that one good eye, as if to say he’d just be on his way now, no need to go to any trouble, really.

The vet adeptly pinned him down and began to prod and massage the cat while speaking about evaluation and x-ray fees, tests for feline leukemia and feline AIDS. She spoke of “surrendering” the animal, which I thought was an odd phrasing, one which obliquely meant death, but which to my mind had come to be conflated with turning oneself in to a federal prison.

I’ve had only one prior experience with euthanizing a family pet. When I was nine, our old gray cat Bruno had become eaten with cancer. One morning, unceremoniously, my father had left for the vet to return some hours later with an empty carrier. Later that evening, after he’d returned from school, my older brother Paul came to me, a can opener in his hand, asking if I’d seen Bruno. It was time for his feeding. Nobody had told him that his beloved pet had been put down that morning. I can recall nothing of my own grief from that time. Rather my memory is that of my brother lying on his bedroom floor, beating the carpet with both fists, crying, “I forgot to feed him this morning! I never fed him! I’m so sorry I forgot to feed you!”

On the drive back to the restaurant I avoided the highway in favor of the backstreets. In the rearview mirror Dalia wiped her sleeve across her face while from the front seat Alicia made soothing sounds.

The restaurant was indeed busy that morning. A cold front had stirred cravings amongst the city dwellers for beef pho. I had to refill the broth pot twice before noon. Then at two o’clock, after the rush, Alicia came to the pass to tell me that her daughters were hungry and could I please make them lunch. In the window I placed a bowl of ramen soup for Dalia and a plate of chicken and rice for Cora. Through the pass I watched the two of them eating at table forty-one. Dalia raised a strand of steaming noodles high above her head. Her face, I noticed with some envy, was dry and smiling.