Sisyphus : On Spring Rolls and Distorted Thinking

Papi fell again, the third time in six months. I was beside him, grabbing a bag of potstickers, when it happened. By the time I’d closed the freezer door, the 77-year-old man was lying sprawled out on the dish pit floor, eyes fluttering, with bits of vermicelli stuck to the side of his face. There’d been something darkly comedic about the tumble. The open freezer door had seemed like a magician’s hanky obscuring a disappearing act. One minute Papi was standing there sipping Pedialyte from a water bottle, the next he was gone. Abracadabra! Now you see him, now you don’t.

I hollered for the other cook and together we lifted the old man and set him on a stool. In Spanish he told us he thought he might have forgotten to take his pills.

He lived in the apartments just beside the restaurant, and I offered to walk him home, but of course he refused. He insisted on finishing his shift. He’d probably been working since the age of eleven, and in that time had only taken, to my knowledge, a single vacation. It was after his second fall, when his wife demanded he take two weeks off. The old man couldn’t understand the concept of a vacation. His adult son had to keep reassuring him that, no, he hadn’t lost his job washing dishes for twelve fifty an hour. It would still be there when he got better.

By the time we’d gotten Papi upright and settled, a reel of unfulfilled tickets had accumulated on the kitchen printer, dangling like a limp streamer after the partygoers had gone: four orders of pho, six plates of fried rice, three bánh mì, four stir-fries. I tore away the tickets, but the unfeeling machine spat out two more.

The fryer sputtered with potstickers, woks with onion and bell pepper. Meanwhile I set about assembling a line of spring rolls, laying down veggies and shrimp on squares of translucent rice paper. In the nearly four years I’ve worked at The Noodle House, I have easily rolled thousands of the things, enough that I often imagine I am Sisyphus with a spring roll as my boulder. The trick to rolling them is to allow enough time for the papers to soften and become pliable, but not so long that they become sticky and liable to tear.

Which is what happened when I took too long tending a fried rice that had begun to burn. One of my rolls split. Vermicelli, cucumber, and pickled carrot hemorrhaged from the rupture. The printer spat out another ticket. From somewhere in the dining room came a peal of drunken laughter. In one swift motion I reared my fist and smashed the offending roll flat. Pink shrimp meat smeared the cutting board like roadkill. The other cook looked over but said nothing.

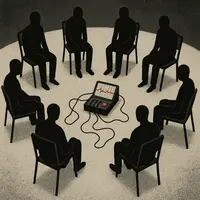

Recently in sex offender treatment we did an exercise on cognitive distortions in which each man was asked to give an example of a thinking error. Midway through, however, the therapist—whose sense of humor leaned towards the passive-aggressive—decided to flip the script and point out our errors himself. He told Jeffrey that believing his grab for the last donut wouldn’t affect his diet was an example of magical thinking. Jason was told that insisting a man cannot rape his wife, and blaming her for his assault charge, was an obvious case of victim stance.

My laughter subsided when it came my turn. I looked pointedly at the therapist from across the circle, daring him to find fault. He returned my gaze. He said that my refusal to leave the restaurant, a job which I admitted made me miserable, was an example of catastrophizing and fortune-telling. Obviously what prevented me from finding other work, he said, was the fear of having to disclose my status as a sex offender to potential employers and facing what I assumed would be certain rejection and failure.

That night after the restaurant had closed, after I’d counted the money and put away the cash drawer, after dismissing the servers and the kitchen crew and putting down the patio umbrellas and locking the doors, I helped Papi empty the dishwasher and put away the last of the pots and pans. In the dark, empty dining room, I polished silverware while Papi finished up in the kitchen, mopping the dish pit floor one last time. I knew his fastidious routine well, could visualize each slow back-and-forth motion of the mop. He’d be untying his apron right about now, his fingers chapped and pink from the hot water and degreaser. It was an apron he’d made himself, sewn together from scrap leather and fishing twine. The sight of his gap-toothed hand stitching always put me in mind of the cracked Tupperware lids that the men in prison would mend with dental floss.

It was true I wanted to get out. It was true I was scared of failure. But it was also true I no longer knew what I wanted to do with my life.

I come from a long line of restaurateurs, beginning with my great-grandfather Aniello who jumped ship to America, settled in Brooklyn and opened a thriving Italian restaurant with his wife Maria. I’d always assumed it was Aniello who was the cook. Only recently did my mother inform me that it was her grandmother who did the cooking while her grandfather managed the front of the house. That was until Maria dropped dead in the kitchen at forty, forcing Aniello behind the stove. Later he would pass down the restaurant to my grandfather who would pass it down to my uncle.

My father, too, was a chef for more than thirty years. I grew up surrounded by food and the business of food. I’d witnessed the labor, the physical and emotional toll. I recalled the long hours and my father’s perpetual absence, arriving home well after I’d been put to bed. His hands still reeked of garlic the next morning when he’d tousle my hair. I decided at an early age that wasn’t the life I wanted for myself. I chose computers instead, trading a chef’s knife and sweaty kitchen for a keyboard and air-conditioned office. It’s ironic that I should have ended up here, at The Noodle House, in the very place I’d worked hard to avoid.

What’s more ironic is that I should be good at cooking. With each passing year I stay at the restaurant, the GM offers another promotion, another modest pay raise to show her appreciation and to squelch the possibility of losing me. On one occasion she told me I am “too good” for the restaurant.

After being locked up for a decade, it is good to feel useful, to be wanted. Another reason I stay.

Back in the dish pit, Papi hung his apron on a peg beside the cup rack and took up his cap and lunch pail. After helping him clock out, I guided him through the dining room by the elbow, his free hand outstretched, groping the dark. At this hour, with the restaurant quiet and the dining room empty of yuppie patrons, and with the bar awash in the soft yellow glow of the Kirin sign, it seemed possible to believe I could be happy here.

Outside, we walked elbow in hand across the trash-strewn parking lot to the light post on the corner where Papi indicated he needed to rest. He braced himself against the post and tilted his head back. Amber light illuminated the flyaway white filaments around his ears, reminding me of my father. They were, I realized, roughly the same age.

We set off across the street only to stop once more just before entering the apartment complex. Here Papi waved me off. He’d agreed to let me walk him home on the condition that I not take him to his front door. His wife would worry if she saw him in distress, and he didn’t want her to call an ambulance.

I nodded and pretended to walk away but continued to follow at a distance of ten yards. Had any insomniac neighbors been out smoking on their balconies, they might have mistaken me for a potential mugger, creeping up behind a stooped and vulnerable old man at two in the morning, a soft insulated lunch pail as his only defense.

I chuckled at the thought and wondered who will walk me home when I am his age.