Detective Brooks : On Guilt, Paranoia, and False Alarms

The phone rings. “Did I wake you?”

It’s my brother, Paul.

“No,” I lie, looking across the room at the clock on the stove—11:42. The day seems half gone. I hadn’t meant to sleep so late, but this past week has been particularly exhausting. The GM at The Noodle House has left on vacation, leaving me in charge. A summer promotion on pho has the restaurant slammed. One of the servers is giving me grief. And the AC in the kitchen is out again, in July no less. Standing before the ovens, all thirteen burners blue-blazing, I feel faint and drugged by the heat. I imagine my body as a misregistered print, my edges doubled and unfocused in magenta and yellow. In the occasional lull between tickets, I abscond to the walk-in to sit and cool on the Asahi kegs and contemplate my place in the world.

“Are you in some kind of trouble?” Paul asks. “Be honest.”

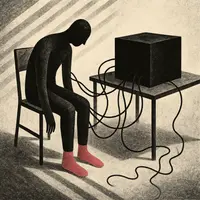

Sometimes I’m not so sure I’m not in trouble. Some mornings it takes several minutes of staring at the ceiling, waiting for the residue of the previous night’s dreams to dissolve and reality to take hold again. The nightmares are always the same: I am at my computer and find pornography but cannot recall how it got there; I am browsing the internet and click on a seemingly innocuous link that leads to porn; or else I click on a link I know full well is porn but cannot help myself. Regardless of the variation, I awake in the morning certain the monitoring software on my computer has flagged the offending material, has notified my probation officer, has alerted the police, and soon there will be a knock on my front door.

But on this particular morning I can recall having no such dream. Yet the concern in Paul’s voice and my grogginess give me pause.

“Trouble?”

“You know, you can tell me anything.”

I sit up in bed, racking my brain for any misdeed. In sex offender treatment we were once asked to rate ourselves on a number of character traits. For energy I gave myself a 2 and for contentment a 3. When asked to score ourselves on guilt, however, the circle seemed in silent agreement that for men in our position—men whose therapist reports directly to their probation officers—there could be only one correct answer. “Zero,” replied each man in turn. They would admit to nothing. When it came my turn, I dissented. “Two,” I said. “I’m always afraid of who I’m letting down.” The therapist looked pleased. “I’m a two myself,” he said.

But aside from my everyday shortcomings, I cannot on this morning think of any recent misconduct, not the legal kind, nothing that would warrant a call from my brother, whom I rarely hear from. “Paul, what are you talking about?”

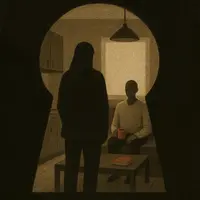

“Heather texted me.” Heather is Paul’s ex-wife. “She says she got a call from a Detective Brooks.”

“Detective who?”

“Detective Brooks. He said he’s an investigator with the Dallas PD. He asked Heather if she’s heard from you and where he can find you.”

“Where to find me? I’m right here!” I stand looking about the room of my studio apartment, mystified that anyone should have trouble finding me. When not here I am at The Noodle House, in the overheated kitchen, or else the cooler sitting atop the beer kegs. My world is a small one. There are only two places I could be—both of which are disclosed on the registry. “But what does this detective want?”

Paul doesn’t know. He says he will call his ex-wife and get more information. He will call me back.

I set my phone down and look once more around the apartment. The bed is still unmade, the blinds closed. The room smells of sleep and is steeped in a disheveled gloom which seems now, in the wake of my brother’s worrisome phone call, to have taken on a new insidious meaning. Once the humble yet comfortable home of the freshly awakened, it is now the den of a hunted animal. Ridiculously, I consider running. From what, I don’t know, as I still can’t think of anything I’ve done wrong or why this Detective Brooks is looking for me. I will run, nevertheless. Because I cannot go back to prison. Not again. Not a third time.

In treatment, the men had gone around the circle revising their scores. Those who’d said they have no guilt reconsidered, in light of the therapist’s approval. A little guilt can be a healthy motivator. Though if I’m honest, my contentment runs at a 2 more than it does a 3, and my guilt is closer to a 3 than a 2. The guilt is like the high whine of an old tube television, always audible in the background and loudest in the quiet spaces between commercials and laugh tracks, constantly begging: Am I a good enough employee, a good enough friend, a good enough brother, a good enough son?

The phone rings again. Paul tells me his ex-wife doesn’t have any more information other than a phone number for the detective, who has asked that I call him immediately. Paul asks again if I can think of any reason why an officer would be looking for me.

“Paul, I haven’t done anything.”

“What about that time at the Home Depot?”

The needle on my guilt meter twitches. He is referring to the time I was hit on in the greenhouse at the local home improvement store by a man pretending to inspect the succulents. He approached me, clearly wearing no underwear. I grabbed him. It happened so long ago I’m dismayed Paul remembers it, let alone that he has chosen to submit it now as evidence.

“Paul, that was two years ago. I came clean to the therapist. I’ve passed four polygraphs since then, one as recent as last month. I haven’t done anything wrong.”

I am sitting at my desk, the phone pressed painfully between my ear and shoulder. On a whim, I pull up a browser window on the computer. Paul’s voice has softened. He is telling me to stay calm. He begins strategizing, telling me what our first move ought to be. We will call this Detective Brooks. We will find out how he got my name and what he wants. We will plan our next step from there. It’s probably nothing …

“It’s a scam, Paul.”

“A what?”

“A scam. I’m looking at it right now. It’s on the internet: ‘There have been multiple reports of a scam involving individuals impersonating a detective named Brooks … The scammers typically contact the victims by phone and falsely claim that there is an active warrant for their arrest, often for charges like failing to register. They then demand payment—’ Paul, it’s a scam.”

I say it again, for his benefit, as well as for my own: “It’s just a scam.”