The Birthday Ritual : Registering as a Sex Offender

Fourteen days before I turned thirty-nine, I drove through the rain to the downtown precinct for my annual sex offender registration, a birthday ritual that—along with renewing my driver’s license—will mark every birthday for the rest of my life.

Registration in Dallas isn’t especially onerous, not compared to hours spent waiting at the DMV. The local police department has streamlined the process, with each day of the week devoted to a certain registration task. Annual registration is on Tuesdays; high-risk offenders who must register every 90 days do so on Thursdays; offenders who need to update a work address, phone number, or any other detail in their records do so on Wednesdays. Mondays are set aside exclusively for the city’s homeless sex offenders, who must report to the precinct every week to give a description of the underpass or street corner where they live.

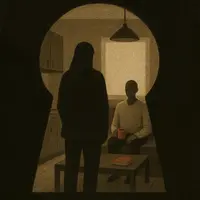

Offenders who report to the precinct to register enter through a recessed door at the back of the building, like help entering through the alley so the guests never see them. That Tuesday I found the door propped open with a cinderblock on account of the steamy rain that had fogged up the lobby inside, condensation dripping from the high windows along the far wall. The room was sparse, furnished only with some folding chairs arranged in three rows beside a receptionist’s window. A cork bulletin board displayed a notice reminding offenders sleeping at the nearby shelter to bring a bed slip proving their residence. Only one other man, wearing scuffed work boots and dungarees, sat waiting. I’d never seen more than three people there at once. I signed in at the receptionist’s window, grabbed a clipboard and pen, and sat down.

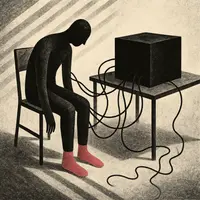

It’s a process I’d been through many times, whether for annual registration or to add a new detail to my record—a license plate number when I bought a car, an email address when my probation officer allowed me to purchase a computer. No matter the transaction, the form was always the same and had to be filled out in full. I’d taken to bringing a copy of past forms and simply copying over the details—driver’s license, VIN, phone numbers, email and social media accounts. Once, on a prior visit, seemingly at random, I was made to submit to fingerprinting and a buccal swab, as if my prints and DNA had somehow changed from the numerous other times they’d been taken in courtrooms, jails, and in prison.

My first experience registering wasn’t in Dallas but in Hutchins, a town just south of the city—little more than a highway exit—where I’d stayed in a halfway house for four months after my release from prison. A counselor from the halfway house, Ms. Iozia, dropped me off at the local police department to register before heading to the Family Dollar across the street. The Hutchins PD occupied a beige, flat-roofed building no bigger than a utility shed, situated off a road only recently paved. Despite having made the mandatory appointment, I sat for half an hour in the lobby, waiting for the officer who would eventually interview, fingerprint, and photograph me.

The lobby—a vestibule, really—was the size of a postage stamp, with space for only two chairs. It held the hushed quiet typical of small, sleepy towns. The silence was so complete I could hear whispered conversation from behind the receptionist’s smoked glass window—a female voice saying, “What is he here for? … Oh, he looks creepy.”

I stared ahead at the wall, face burning. That morning I’d put on my nicest pants and shirt—clothes my mother had sent me because I owned none of my own. I’d carefully trimmed my beard, too, with the razor I’d brought from prison, a Gillette purchased years earlier at the commissary. I had consciously tried to present myself as an ordinary, upstanding citizen.

Oh, he looks creepy.

Ms. Iozia was waiting for me in her car when I got out an hour later. She’d been right to go shopping. She said we would take the long way back to the halfway house, and so we did, over winding country back roads with no paved shoulders. We talked. She told me about her work as a counselor, about her family, her kids. Back on the service road she stopped at a McDonald’s drive-thru and bought me a quarter-pounder with cheese and a small Coke and told me not to tell anyone.

“You must be tired of all that prison food,” she’d said.

I finished filling out the forms, returned the clipboard, and sat back down. An officer entered the steamy lobby and called on the man in dungarees to sign and initial some papers. He then directed the man to stand on footprint decals against the wall to have his photograph taken.

“See you next year,” he told the man as he walked out the open door and into the drizzle.

Then it was my turn. I signed and initialed the necessary forms, and when asked to pose for my photograph, I arranged my face in the same expression I’d worn earlier in the month for my driver’s license renewal: a half smile, lips relaxed, brows and chin raised slightly—what I imagined to be the expression of an ordinary, upstanding citizen.