Denial : A Year of Silence and Survival

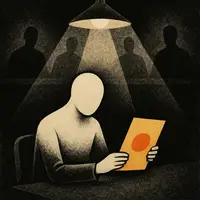

I didn’t immediately tell anyone about the interrogation by the FBI. I stayed silent for almost a year while the investigation took place.

In that time, I became an expert at suppressing reality, both from loved ones and myself. I told my parents and boyfriend that I’d accidentally dropped my computer and it had broken. In reality, the FBI had confiscated it along with every hard drive in my apartment.

After the interrogation, I could no longer stand being alone in my apartment, or anywhere for that matter. I’d sit and read at nearby coffee shops until they closed. I’d find excuses to stay late at work and bury myself in projects that were of no real urgency. I’d leave the radio on to keep me company. I knew it wasn’t a healthy way of coping, but it was the best way I knew to survive. The alternative—to have admitted to people what I’d done—hadn’t seemed an option. I was sure my friends and family wouldn’t have understood, or worse, they might have abandoned me.

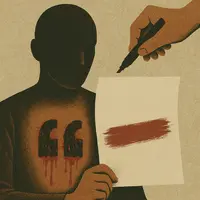

Suicidal thoughts became routine. Every day while driving to work I imagined jumping from the nearest downtown high rise. I recalled a friend once telling me that eight stories was the maximum height at which a person could fall and still survive. If I did decide to jump, I’d make sure it was more than eight stories—ten for safe measure.

I’d also heard somewhere that when a person dies, they may shit or piss themselves. So I decided in the event of Plan B, I’d make sure to kill myself on an empty stomach. There isn’t much dignity in suicide, so they say, but I figured I’d at least keep it clean.

I knew I’d never carry out any of these fantasies, but it was comforting to know there was always that Plan B, an escape hatch that I might open if things got too difficult. Death was the only thing I felt I had any control over.

It wasn’t until I received the target letter from the Justice Department in September of 2010 that I decided I had to come clean.